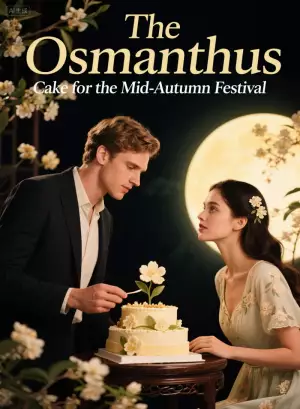

The Osmanthus Cake for the Mid-Autumn Festival

I stood downstairs, watching the setting sun dye the glass curtain wall in warm shades of gold.

The autumn wind swept a few sycamore leaves, which drifted slowly onto the tips of my black leather shoes.

The tip of my shoe was dusted with a bit of dirt, brushed against the roadside by the crowd while queuing to buy Osmanthus Cake this morning.

Today is the Mid-Autumn Festival; most people on the street carry gift boxes, hastening home with hurried steps.

A man in a plaid shirt held two boxes of mooncakes and cradled a sleeping child, carefully avoiding the crowd—the sight bore a striking resemblance to my father back then.

I, too, held a kraft paper bag in my hand; inside were Blair Scott's favorite Osmanthus Cakes.

The corner of the paper bag was tightly wrinkled in my grasp—not from nervousness, but because it reminded me how, twenty years ago, my mother held my hand just like this, tucking freshly bought Osmanthus Cakes close to her chest, saying she would wait for me to finish the mooncake before giving me the cakes as a snack.

This morning, I deliberately took a detour to the old town to buy it, standing in line for a full forty minutes.

An old lady ahead kept murmuring to the cake seller, "My granddaughter loves your cakes," for three whole minutes. Standing behind, my ears filled with the echo of my mother's voice from years ago.

Blair Scott always said that the Osmanthus Cakes from chain bakeries were too sweet and cloying; only the old brand at the end of the alley truly captured the flavor.

When she first mentioned it to me, I was stunned for a long moment—that was the very shop my parents had taken me to back then. After I was sent to the welfare home, I never returned.

My fingertips brushed against the paper bag, feeling the warm shape of the Osmanthus Cake.

But only I knew what kind of poisoned intentions lay hidden within that soft sweetness.

Just as Lily once smiled, handing me a piece of candy before turning and crashing into my parents with her car.

My phone vibrated — a message from Blair Scott: "Yale, where are you? Mom has laid out the dishes."

I replied, "Almost there," then tucked the phone back into my pocket.

The screen was still glowing; the lock screen was a photo Blair Scott took last Mid-Autumn Festival.

She leaned against my shoulder, her eyes crescent-shaped with a smile, while my face remained expressionless, forced by her to twitch the corners of my lips.

I lifted my head to gaze at the distant moon, just beginning to emerge, like a piece of jade veiled in thin silk.

Clouds drifted across, concealing part of the moon, much like the moonlight slipping through the gaps between my fingers as I covered my face and wept after the car accident back then.

Twenty years ago on the Mid-Autumn Festival, the moon was just as full.

That day, I wore new sneakers that my father had bought after saving half a month's wages; the white uppers embroidered with a little tiger.

I tugged at my parents' hands, eager to buy mooncakes. Father said he would get me the lotus seed paste with salted egg yolk flavor, and mother laughed.

As we passed beneath the osmanthus tree on the street corner, my mother plucked a small sprig of blossoms and pinned it to my collar, saying, "You should carry a sweet fragrance; then when you go to kindergarten, others will want to play with you."

I pressed that sprig of osmanthus between the pages of my textbook. It was only when the staff at the welfare home sorted through my belongings that they discovered it had long since withered into fragments.

But after that day, I never smelled the scent of osmanthus again.

As I hailed a taxi, the driver was humming a tune.

Rolling down the window, he smiled and asked, "Young man, going home for the Mid-Autumn Festival? I see you're carrying cakes—those must be for your family, right?"

I clenched the paper bag tightly and muttered a vague "Mm."

The driver didn't notice my unease and continued chatting: "After this ride today, I'll head home. My daughter's waiting for me to eat mooncakes—she insists on the five-nut kind, saying it tastes just like when she was little."

When he spoke of his daughter, the laughter in the corners of his eyes was impossible to hide.

I watched the streets flash past outside the window and recalled how my father was just the same—chatting with the taxi driver about my embarrassing moments, saying, "My son insisted on wearing new sneakers today; otherwise, he wouldn't come along with me."

The car passed through the intersection just as the red light turned on.

A Mercedes was parked in the adjacent lane, remarkably similar to the model Lily used to drive years ago.

I stared at the car, my fingers absentmindedly fidgeting with the seat until the driver said, "The light's green," snapping me back to reality—after all these years, I realize familiar scenes can still wound me.

The taxi stopped at the gate of the residential compound, and the security guard smiled, nodding to me: "Mr. Lincoln, happy Mid-Autumn Festival."

He held an apple, a gift from one of the residents. I recall last year he complained to me, "The Scott family gives so few benefits," but this year he smiled at me—likely because Howard Scott had promoted his son.

I replied, "Same to you," and carried the paper bag as I walked inside.

The neighborhood was hung with red lanterns, and children were playing with Rabbit lanterns on the lawn.

A little girl with pigtails ran past holding a lantern and nearly bumped into me.

Her mother quickly pulled her back, saying, "Slow down."

The little girl looked up, blinking her big eyes, and asked me, "Are you here to celebrate the festival too?"

Around her neck hung a longevity token necklace, exactly like the one I had back then—my mother's dowry that disappeared after the car accident. Later, I once saw it in Lily's jewelry box, and she said it was a "little trinket she had picked up on the street."

I paused, remembering myself twenty years ago, running around my parents just the same, waving my Rabbit lantern and shouting, "Dad, catch me!"

I forced out a stiff smile: "Yes, I'm here for the festival too."

After the little girl ran off, I touched the Paraquat bottle in my pocket—the coldness steadied me—I wasn't here to celebrate, but to send them to hell.

As I reached the Scott family villa's door, it opened from the inside.

Blair Scott, wearing an off-white dress, rushed over and hooked her arm through mine: "Yale, you finally made it!"

On her wrist was a silver bracelet—the birthday gift I gave her last year. It cost me three months' salary, all so she would believe I was truly sincere with her. I even fell behind on a month's rent because of it.

She wore a strong scent of perfume—the lily fragrance I hated most. It was the very scent Lily had when she left the police station that year.

That day, I hid behind the tree at the welfare home's gate, watching her get picked up by Howard Scott. The perfume drifted for dozens of meters, like a needle piercing my eyes with pain.

I held back my frown and reached up to smooth her hair. 'The road's a bit congested,' I said.

Her hair was soft, like the kitten I raised in my childhood—yet that kitten was later killed by children from the welfare home, just as the Scott family destroyed every ounce of my gentleness.

At the entrance stood a glass cabinet displaying Lily's "honors"—various charity trophies, along with a photograph of her with government officials.

In that photograph, she smiled with elegant composure, holding a plaque inscribed "Compassionate Entrepreneur," but I can never forget the coldness in her eyes when she didn't even glance in the rearview mirror as our parents were dragged beneath the car.

As soon as I stepped in, Lily hurried over and guided me toward the dining room.

She wore a silk dress, the pearl necklace around her neck swinging and making me dizzy. "Yale, sit . All these dishes tonight were made by my own hands."

The dress's buttons were jade; I looked it up—they're worth over a hundred thousand, enough for my parents to have bought a small house back then.

The dining table was long, draped in a white tablecloth, with a fruit plate in the center holding sliced mooncakes—all filled with lotus seed paste and salted egg yolk, my favorite flavor back then, but now, just looking at them made me feel sick.

Last year during the Mid-Autumn Festival, Blair Scott brought a mooncake to my lips. I forced myself to swallow it, and that night I vomited in the bathroom for hours.

Howard Scott sat at the head of the table, holding a purple clay teapot, slowly pouring tea: "Yale, you're here."

The teapot was a master's handcrafted piece—I had seen the identical one in an antique shop, priced at half a million.

His tea-pouring was elegant, yet I remembered how, back when he was at the police station, he pounded the table and shouted at the officers, “I am rich; don't meddle in my affairs.”

I nodded and sat down beside Blair Scott.

No sooner had I settled down than Lily pushed a velvet box toward me.

Opening it, I found a silver car key inside, engraved with the Porsche emblem.

The keychain was a small moon, identical to the pendant around Blair Scott's neck—she always said, "The moon represents my heart," though she did not know my heart had long since grown cold beneath its light.

"Yale, I didn't know what car you liked, so I just picked one at random."

Lily smiled, crow's feet forming at the corners of her eyes. "You work hard squeezing into the subway every day; from now on, just drive this."

She paused, then added, "The company will reimburse the fuel expenses. You don't need to worry about it."

I clenched the keys, the cold metal digging into my palm.

Last winter, when my fever soared to 39 degrees and I squeezed onto the subway to get to the hospital, Lily still said, "Young people just have to tough it out; don't waste money on a taxi."

That day, I nearly fainted on the subway. A stranger gave up her seat for me, and now, looking back, it felt far warmer than the so-called 'kindness' from the Scott family.

Howard Scott then slid a document across the table, its cover bearing the title 'Equity Transfer Agreement.'

He tapped his fingers on the document. "Yale, you've been married into the Scott family for three years now. You've been reliable, so I trust you."

He took a sip of tea, his eyes filled with calculation. "Take these shares. One day, the Scott Group will have a place for you too—though we must wait until Blair has the baby."

Speaking, he gently patted the back of my hand. "We both long to hold our grandchild—preferably a boy, so he can someday inherit the family business."

I looked at his hypocritical smile and recalled how my parents never even saw me grow up. The bitterness within me deepened once again.

Blair Scott leaned against my shoulder, her voice sweet: "Honey, from now on, we're going to be rich!"

Her fingers traced circles on the back of my hand. "When we have a baby, let's name her 'Nina,' okay?"

She was lost in her own daydreams, unaware of the coldness flickering in my eyes.

I nodded in response to her words: "Alright, whatever you say."

But inside, I sneered—none of you will see the day the child is born, nor this so-called 'romantic future.'

I watched the hopeful look in their little family's eyes and smiled bitterly within.

Yes, rich people.

Twenty years ago, you did the same—crushing my parents' lives to nothing but ashes.

Halfway through the meal, Lily suddenly took out an old box, inside which lay a black Mercedes-Benz car key.

The paint was chipped on the key, and I recognized it immediately—that was the very car that killed my parents. I'd seen it countless times in photos at the police station.

"Look at me," she laughed, tossing the key onto the table. "That old car had a little accident back then. Luckily, it was settled with money."

When she said "a little accident," she picked up a pair of chopsticks to take some braised pork, chewing it with delight, as if telling some trivial, unimportant story.

The chopsticks in my hand faltered; my grip on the edge of the celadon bowl turned white with tension.

My knuckles, strained from gripping, turned bluish-purple—I remembered how, back then in the morgue, my parents' fingers were just like this, cold and stiff.

Blair Scott didn't notice my unease and picked up the keys, fiddling with them: "Mom, this car should have been scrapped long ago—it's so old."

She spun the keys around in her hand; the little bell on the keychain jingled once, yet to me, it sounded like the cries of Mom and Dad.

Howard Scott frowned. "Don't throw it away. Keep it. Back then, when Lily drove this car, she closed several big deals—it was a good luck charm."

He spoke lightly, but I knew that on the wheels of that "good luck charm," my parents' blood was stained.

Lily patted Blair Scott's hand. "This is a limited edition from those years, kept as a memento."

She handed me a piece of rib. "Yale, eat. Don't just stand there—I've stewed these ribs for four hours."

I took a deep breath and swallowed the braised pork in my bowl—the meat was greasy, like hatred lodged in my throat.

As I swallowed, my stomach roiled like a raging sea, yet I still had to wear the smile of someone "humbly honored."

Nanny Linda came over carrying a plate of steamed fish and placed it on the table.

She was the Scott family's nanny, having served them for ten years, a truly honest woman.

Her apron was stained with fish juices, splattered while she cleaned the fish moments before—she always said, "The fish are fresh. Don’t worry and eat."

Last winter, when I had a fever, everyone in the Scott family went to a business party; only Nanny Linda stayed behind to make ginger soup for me.

When she brought the ginger soup to my room, she carefully wrapped the bottom of the bowl with a towel, afraid it might burn me: "Mr. Lincoln, it's not easy for you to work. If anything happens, don't try to bear it all by yourself. Talk to me."

That day, as I sipped the ginger soup, a warmth slid down my throat to my stomach, yet the hatred in my heart felt as cold as ice.

I looked at her hands, reddened by the cold, and for the first time, I felt a flicker of doubt—perhaps there were still good people in this world.

But when I thought of how Mom and Dad lay in the morgue, that flicker of doubt was crushed once more beneath the weight of my hatred.

I cannot soften my heart; to do so would be to betray Mom and Dad.

Seeing me, Nanny Linda smiled softly, "Mr. Lincoln, Happy Mid-Autumn Festival."

Her smile was simple and genuine, devoid of Lily's falsehood and Blair Scott's indulgence.

I nodded at her. "Nanny Linda, please sit down and have some as well."

I knew she didn't dare to sit, but I still wanted to say—at least with me, she didn't have to keep her head bowed all the time, like she did in front of the members of the Scott family.

Lily waved her hand, "No, no, let her finish. We'll eat first."

When she spoke, she didn't even look at Nanny Linda, as if speaking to an inanimate object.

Nanny Linda said nothing and turned around, slipping back into the kitchen.

I watched her retreating figure, a tight knot forming in my chest.

The one I owe the deepest apology to this time is her.

I even wondered—if she hadn't been home today, would I have been spared from this disaster? Yet I needed her help to 'cover up' the Paraquat incident—I was, in the end, exploiting her kindness.

After dinner, I made an excuse to visit the restroom and rose to head toward the kitchen.

The family portrait of the Scott family hung on the corridor wall—Howard Scott and Lily sat in the center, with Blair Scott standing beside them, her face alight with a happy smile.

Beneath the photo were the words "Happy Home." As I looked at those four characters, I felt nothing but bitter irony.

Nanny Linda was washing the dishes, the faucet barely turned on. She always said, "Save water; every little drop counts."

The sink was piled high with dishes, all used by us just moments before. She washed with meticulous care, even wiping the grease from the rims until they gleamed.

Hearing footsteps, Nanny Linda glanced back at me. "Mr. Lincoln, is something wrong?"

She held a sponge in her hand, still covered with frothy detergent.

I shook my head. "Nothing. I just wanted to help you."

I pointed toward the garage, trying to keep my tone as natural as possible.

On the kitchen windowsill sat a tube of hand cream—Blair Scott had bought it for me a few days ago, saying my hands would crack from washing dishes in winter.

When she handed it to me, she squeezed a little onto my hand and said, "Darling, you have to take good care of your hands. You still need to peel shrimp for me in the future."

That day, her fingers felt so soft, but to me, they seemed like a serpent's fang—cold and dangerous.

I picked up the hand cream; my fingertips touched the cold bottle, and I recalled Blair Scott's smile when she gave it to me.

At that moment, I felt a little dazed.

Blair Scott hadn't really done anything wrong; she was simply born into the Scott family, inheriting their coldness and selfishness.

But I had no choice. From the day my parents fell into a pool of blood, all I had left was revenge—none of the Scott family members could be spared.

I put the hand cream back where it belonged, unscrewed the cap of the paraquat, and the sound of the poison dripping into the sink was piercingly loud in the quiet kitchen.

The autumn wind swept a few sycamore leaves, which drifted slowly onto the tips of my black leather shoes.

The tip of my shoe was dusted with a bit of dirt, brushed against the roadside by the crowd while queuing to buy Osmanthus Cake this morning.

Today is the Mid-Autumn Festival; most people on the street carry gift boxes, hastening home with hurried steps.

A man in a plaid shirt held two boxes of mooncakes and cradled a sleeping child, carefully avoiding the crowd—the sight bore a striking resemblance to my father back then.

I, too, held a kraft paper bag in my hand; inside were Blair Scott's favorite Osmanthus Cakes.

The corner of the paper bag was tightly wrinkled in my grasp—not from nervousness, but because it reminded me how, twenty years ago, my mother held my hand just like this, tucking freshly bought Osmanthus Cakes close to her chest, saying she would wait for me to finish the mooncake before giving me the cakes as a snack.

This morning, I deliberately took a detour to the old town to buy it, standing in line for a full forty minutes.

An old lady ahead kept murmuring to the cake seller, "My granddaughter loves your cakes," for three whole minutes. Standing behind, my ears filled with the echo of my mother's voice from years ago.

Blair Scott always said that the Osmanthus Cakes from chain bakeries were too sweet and cloying; only the old brand at the end of the alley truly captured the flavor.

When she first mentioned it to me, I was stunned for a long moment—that was the very shop my parents had taken me to back then. After I was sent to the welfare home, I never returned.

My fingertips brushed against the paper bag, feeling the warm shape of the Osmanthus Cake.

But only I knew what kind of poisoned intentions lay hidden within that soft sweetness.

Just as Lily once smiled, handing me a piece of candy before turning and crashing into my parents with her car.

My phone vibrated — a message from Blair Scott: "Yale, where are you? Mom has laid out the dishes."

I replied, "Almost there," then tucked the phone back into my pocket.

The screen was still glowing; the lock screen was a photo Blair Scott took last Mid-Autumn Festival.

She leaned against my shoulder, her eyes crescent-shaped with a smile, while my face remained expressionless, forced by her to twitch the corners of my lips.

I lifted my head to gaze at the distant moon, just beginning to emerge, like a piece of jade veiled in thin silk.

Clouds drifted across, concealing part of the moon, much like the moonlight slipping through the gaps between my fingers as I covered my face and wept after the car accident back then.

Twenty years ago on the Mid-Autumn Festival, the moon was just as full.

That day, I wore new sneakers that my father had bought after saving half a month's wages; the white uppers embroidered with a little tiger.

I tugged at my parents' hands, eager to buy mooncakes. Father said he would get me the lotus seed paste with salted egg yolk flavor, and mother laughed.

As we passed beneath the osmanthus tree on the street corner, my mother plucked a small sprig of blossoms and pinned it to my collar, saying, "You should carry a sweet fragrance; then when you go to kindergarten, others will want to play with you."

I pressed that sprig of osmanthus between the pages of my textbook. It was only when the staff at the welfare home sorted through my belongings that they discovered it had long since withered into fragments.

But after that day, I never smelled the scent of osmanthus again.

As I hailed a taxi, the driver was humming a tune.

Rolling down the window, he smiled and asked, "Young man, going home for the Mid-Autumn Festival? I see you're carrying cakes—those must be for your family, right?"

I clenched the paper bag tightly and muttered a vague "Mm."

The driver didn't notice my unease and continued chatting: "After this ride today, I'll head home. My daughter's waiting for me to eat mooncakes—she insists on the five-nut kind, saying it tastes just like when she was little."

When he spoke of his daughter, the laughter in the corners of his eyes was impossible to hide.

I watched the streets flash past outside the window and recalled how my father was just the same—chatting with the taxi driver about my embarrassing moments, saying, "My son insisted on wearing new sneakers today; otherwise, he wouldn't come along with me."

The car passed through the intersection just as the red light turned on.

A Mercedes was parked in the adjacent lane, remarkably similar to the model Lily used to drive years ago.

I stared at the car, my fingers absentmindedly fidgeting with the seat until the driver said, "The light's green," snapping me back to reality—after all these years, I realize familiar scenes can still wound me.

The taxi stopped at the gate of the residential compound, and the security guard smiled, nodding to me: "Mr. Lincoln, happy Mid-Autumn Festival."

He held an apple, a gift from one of the residents. I recall last year he complained to me, "The Scott family gives so few benefits," but this year he smiled at me—likely because Howard Scott had promoted his son.

I replied, "Same to you," and carried the paper bag as I walked inside.

The neighborhood was hung with red lanterns, and children were playing with Rabbit lanterns on the lawn.

A little girl with pigtails ran past holding a lantern and nearly bumped into me.

Her mother quickly pulled her back, saying, "Slow down."

The little girl looked up, blinking her big eyes, and asked me, "Are you here to celebrate the festival too?"

Around her neck hung a longevity token necklace, exactly like the one I had back then—my mother's dowry that disappeared after the car accident. Later, I once saw it in Lily's jewelry box, and she said it was a "little trinket she had picked up on the street."

I paused, remembering myself twenty years ago, running around my parents just the same, waving my Rabbit lantern and shouting, "Dad, catch me!"

I forced out a stiff smile: "Yes, I'm here for the festival too."

After the little girl ran off, I touched the Paraquat bottle in my pocket—the coldness steadied me—I wasn't here to celebrate, but to send them to hell.

As I reached the Scott family villa's door, it opened from the inside.

Blair Scott, wearing an off-white dress, rushed over and hooked her arm through mine: "Yale, you finally made it!"

On her wrist was a silver bracelet—the birthday gift I gave her last year. It cost me three months' salary, all so she would believe I was truly sincere with her. I even fell behind on a month's rent because of it.

She wore a strong scent of perfume—the lily fragrance I hated most. It was the very scent Lily had when she left the police station that year.

That day, I hid behind the tree at the welfare home's gate, watching her get picked up by Howard Scott. The perfume drifted for dozens of meters, like a needle piercing my eyes with pain.

I held back my frown and reached up to smooth her hair. 'The road's a bit congested,' I said.

Her hair was soft, like the kitten I raised in my childhood—yet that kitten was later killed by children from the welfare home, just as the Scott family destroyed every ounce of my gentleness.

At the entrance stood a glass cabinet displaying Lily's "honors"—various charity trophies, along with a photograph of her with government officials.

In that photograph, she smiled with elegant composure, holding a plaque inscribed "Compassionate Entrepreneur," but I can never forget the coldness in her eyes when she didn't even glance in the rearview mirror as our parents were dragged beneath the car.

As soon as I stepped in, Lily hurried over and guided me toward the dining room.

She wore a silk dress, the pearl necklace around her neck swinging and making me dizzy. "Yale, sit . All these dishes tonight were made by my own hands."

The dress's buttons were jade; I looked it up—they're worth over a hundred thousand, enough for my parents to have bought a small house back then.

The dining table was long, draped in a white tablecloth, with a fruit plate in the center holding sliced mooncakes—all filled with lotus seed paste and salted egg yolk, my favorite flavor back then, but now, just looking at them made me feel sick.

Last year during the Mid-Autumn Festival, Blair Scott brought a mooncake to my lips. I forced myself to swallow it, and that night I vomited in the bathroom for hours.

Howard Scott sat at the head of the table, holding a purple clay teapot, slowly pouring tea: "Yale, you're here."

The teapot was a master's handcrafted piece—I had seen the identical one in an antique shop, priced at half a million.

His tea-pouring was elegant, yet I remembered how, back when he was at the police station, he pounded the table and shouted at the officers, “I am rich; don't meddle in my affairs.”

I nodded and sat down beside Blair Scott.

No sooner had I settled down than Lily pushed a velvet box toward me.

Opening it, I found a silver car key inside, engraved with the Porsche emblem.

The keychain was a small moon, identical to the pendant around Blair Scott's neck—she always said, "The moon represents my heart," though she did not know my heart had long since grown cold beneath its light.

"Yale, I didn't know what car you liked, so I just picked one at random."

Lily smiled, crow's feet forming at the corners of her eyes. "You work hard squeezing into the subway every day; from now on, just drive this."

She paused, then added, "The company will reimburse the fuel expenses. You don't need to worry about it."

I clenched the keys, the cold metal digging into my palm.

Last winter, when my fever soared to 39 degrees and I squeezed onto the subway to get to the hospital, Lily still said, "Young people just have to tough it out; don't waste money on a taxi."

That day, I nearly fainted on the subway. A stranger gave up her seat for me, and now, looking back, it felt far warmer than the so-called 'kindness' from the Scott family.

Howard Scott then slid a document across the table, its cover bearing the title 'Equity Transfer Agreement.'

He tapped his fingers on the document. "Yale, you've been married into the Scott family for three years now. You've been reliable, so I trust you."

He took a sip of tea, his eyes filled with calculation. "Take these shares. One day, the Scott Group will have a place for you too—though we must wait until Blair has the baby."

Speaking, he gently patted the back of my hand. "We both long to hold our grandchild—preferably a boy, so he can someday inherit the family business."

I looked at his hypocritical smile and recalled how my parents never even saw me grow up. The bitterness within me deepened once again.

Blair Scott leaned against my shoulder, her voice sweet: "Honey, from now on, we're going to be rich!"

Her fingers traced circles on the back of my hand. "When we have a baby, let's name her 'Nina,' okay?"

She was lost in her own daydreams, unaware of the coldness flickering in my eyes.

I nodded in response to her words: "Alright, whatever you say."

But inside, I sneered—none of you will see the day the child is born, nor this so-called 'romantic future.'

I watched the hopeful look in their little family's eyes and smiled bitterly within.

Yes, rich people.

Twenty years ago, you did the same—crushing my parents' lives to nothing but ashes.

Halfway through the meal, Lily suddenly took out an old box, inside which lay a black Mercedes-Benz car key.

The paint was chipped on the key, and I recognized it immediately—that was the very car that killed my parents. I'd seen it countless times in photos at the police station.

"Look at me," she laughed, tossing the key onto the table. "That old car had a little accident back then. Luckily, it was settled with money."

When she said "a little accident," she picked up a pair of chopsticks to take some braised pork, chewing it with delight, as if telling some trivial, unimportant story.

The chopsticks in my hand faltered; my grip on the edge of the celadon bowl turned white with tension.

My knuckles, strained from gripping, turned bluish-purple—I remembered how, back then in the morgue, my parents' fingers were just like this, cold and stiff.

Blair Scott didn't notice my unease and picked up the keys, fiddling with them: "Mom, this car should have been scrapped long ago—it's so old."

She spun the keys around in her hand; the little bell on the keychain jingled once, yet to me, it sounded like the cries of Mom and Dad.

Howard Scott frowned. "Don't throw it away. Keep it. Back then, when Lily drove this car, she closed several big deals—it was a good luck charm."

He spoke lightly, but I knew that on the wheels of that "good luck charm," my parents' blood was stained.

Lily patted Blair Scott's hand. "This is a limited edition from those years, kept as a memento."

She handed me a piece of rib. "Yale, eat. Don't just stand there—I've stewed these ribs for four hours."

I took a deep breath and swallowed the braised pork in my bowl—the meat was greasy, like hatred lodged in my throat.

As I swallowed, my stomach roiled like a raging sea, yet I still had to wear the smile of someone "humbly honored."

Nanny Linda came over carrying a plate of steamed fish and placed it on the table.

She was the Scott family's nanny, having served them for ten years, a truly honest woman.

Her apron was stained with fish juices, splattered while she cleaned the fish moments before—she always said, "The fish are fresh. Don’t worry and eat."

Last winter, when I had a fever, everyone in the Scott family went to a business party; only Nanny Linda stayed behind to make ginger soup for me.

When she brought the ginger soup to my room, she carefully wrapped the bottom of the bowl with a towel, afraid it might burn me: "Mr. Lincoln, it's not easy for you to work. If anything happens, don't try to bear it all by yourself. Talk to me."

That day, as I sipped the ginger soup, a warmth slid down my throat to my stomach, yet the hatred in my heart felt as cold as ice.

I looked at her hands, reddened by the cold, and for the first time, I felt a flicker of doubt—perhaps there were still good people in this world.

But when I thought of how Mom and Dad lay in the morgue, that flicker of doubt was crushed once more beneath the weight of my hatred.

I cannot soften my heart; to do so would be to betray Mom and Dad.

Seeing me, Nanny Linda smiled softly, "Mr. Lincoln, Happy Mid-Autumn Festival."

Her smile was simple and genuine, devoid of Lily's falsehood and Blair Scott's indulgence.

I nodded at her. "Nanny Linda, please sit down and have some as well."

I knew she didn't dare to sit, but I still wanted to say—at least with me, she didn't have to keep her head bowed all the time, like she did in front of the members of the Scott family.

Lily waved her hand, "No, no, let her finish. We'll eat first."

When she spoke, she didn't even look at Nanny Linda, as if speaking to an inanimate object.

Nanny Linda said nothing and turned around, slipping back into the kitchen.

I watched her retreating figure, a tight knot forming in my chest.

The one I owe the deepest apology to this time is her.

I even wondered—if she hadn't been home today, would I have been spared from this disaster? Yet I needed her help to 'cover up' the Paraquat incident—I was, in the end, exploiting her kindness.

After dinner, I made an excuse to visit the restroom and rose to head toward the kitchen.

The family portrait of the Scott family hung on the corridor wall—Howard Scott and Lily sat in the center, with Blair Scott standing beside them, her face alight with a happy smile.

Beneath the photo were the words "Happy Home." As I looked at those four characters, I felt nothing but bitter irony.

Nanny Linda was washing the dishes, the faucet barely turned on. She always said, "Save water; every little drop counts."

The sink was piled high with dishes, all used by us just moments before. She washed with meticulous care, even wiping the grease from the rims until they gleamed.

Hearing footsteps, Nanny Linda glanced back at me. "Mr. Lincoln, is something wrong?"

She held a sponge in her hand, still covered with frothy detergent.

I shook my head. "Nothing. I just wanted to help you."

I pointed toward the garage, trying to keep my tone as natural as possible.

On the kitchen windowsill sat a tube of hand cream—Blair Scott had bought it for me a few days ago, saying my hands would crack from washing dishes in winter.

When she handed it to me, she squeezed a little onto my hand and said, "Darling, you have to take good care of your hands. You still need to peel shrimp for me in the future."

That day, her fingers felt so soft, but to me, they seemed like a serpent's fang—cold and dangerous.

I picked up the hand cream; my fingertips touched the cold bottle, and I recalled Blair Scott's smile when she gave it to me.

At that moment, I felt a little dazed.

Blair Scott hadn't really done anything wrong; she was simply born into the Scott family, inheriting their coldness and selfishness.

But I had no choice. From the day my parents fell into a pool of blood, all I had left was revenge—none of the Scott family members could be spared.

I put the hand cream back where it belonged, unscrewed the cap of the paraquat, and the sound of the poison dripping into the sink was piercingly loud in the quiet kitchen.

Download the SnackShort app, Search 【 790174 】reads the whole book.

My Fiction

NovelShort

« Previous Post

Ashes of Betrayal and Revenge

Next Post »

Signing Divorce on the Day of Miscarriage